Info ladies crisscross the countryside offering the chance to see a loved one, get a blood sugar check or even legal advice

Bangladeshi info

ladies in Saghata, a remote impoverished farming village in Gaibandha

district, Bangladesh. Photograph: AM Ahad/AP

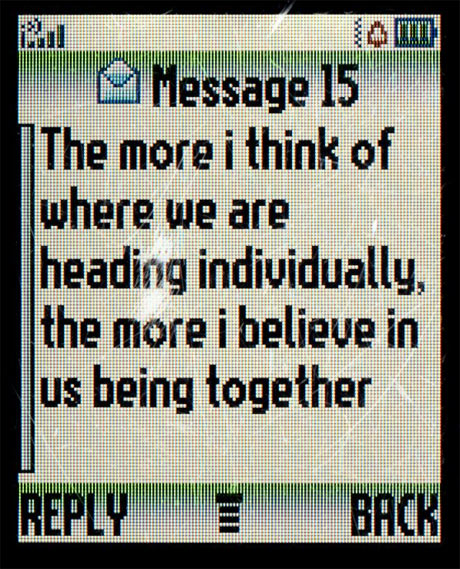

As she approaches the village, Sathi rings her bicycle bell and

the children come running to meet her, shouting "Hello, hello". Women

emerge from their homes one by one. Sitting in the middle of a

beaten-earth yard, Sathi carefully places her laptop on a plastic chair,

plugs in headphones and launches a session on Skype. The faces of

village men working thousands of kilometres from here appear on the

screen.

"It's like my brother was standing right there, except I

can't touch him. What's more he's put on weight and lost colour since he

started work in Iraq," says a worried Sumita. She keeps saying

"As-salamu alaykum" and "Hello", for fear he might vanish. "It's a bad

connection," Sathi explains. "It's a public holiday and everyone wants

to call the Gulf states, so it's busy."

A session costs a fortune,

equivalent to about $3 an hour. "But the price includes technical

support or volume adjustment," Sathi adds. Even at this price Skype is a

great success. In Bangladesh, population 152 million, only 5 million people are connected.

So

56 "info ladies" crisscross the countryside, dressed in blue and pink

uniform and carrying in their bags a laptop, a camera to make films or

take wedding snaps, but also tests for blood sugar and pregnancy, and of

course some cosmetics and shampoo. Thanks to their PC connected to the

"new world" via a USB stick, these women can call up information beyond

the reach of village schoolteachers. Internet access is an instrument of

emancipation too. The women advise farmers and sometimes even offer

legal advice.

Information needs these "ladies" to reach its

destination, because "browsing the net is like flying a rocket to land

on another planet", Sathi says. "It scares lots of people." But

technology is not only for those who know how to use it; it's also for

those who want to appropriate it. The women swap helpful advice and

sometimes spend whole nights solving a technical hitch. The D.net non-profit organisation [PDF],

which launched the scheme in 2008, trains the women for three months on

how to use the hardware, at centres close to their home. To start their

business they need to take out a loan: roughly $650.

They make an

early start. At 6am Jeyasmin prepares a meal outside her hut,

consisting mainly of rice, then takes her daughter to school. When she

returns men are already waiting anxiously, eager to check their blood

sugar. Ever since Jeyasmin organised a session on this subject, many of

the residents think they have diabetes. "Villagers are not generally

ready to purchase information, so the ladies sell them accompanying

services, like medical tests or natural fertilisers," D.net head Ananya

Raihan explains. A few hours later several teenage women are waiting for

Jeyasmin in the shade of a date tree. She shows them a video, with

white-coated experts talking and pointing to animated graphics over

their heads. "Doctors never come to see us, so we might as well watch

them on a PC. But it's a pity they don't answer our questions," says one

of the young women. When Jeyasmin takes out her weighing machine, it

draws a big crowd. They climb on to the machine, standing tall and not

batting an eyelid, for fear of upsetting it.

Many of the younger

women confide in the info ladies. "They understand our worries and don't

make judgments," says one of them. Some teenagers even ask the women to

buy them underwear, sanitary towels and makeup in town, because

generally only the men go to market. The purveyors of information also

have what they call their "Facebook secrets", or indeed the Skype

equivalent. After creating a Facebook account, Golapi Akter met a

Bangladeshi who lives in Dubai. "There are so many men who live in

Facebook," she whispers. She chats with him every week on Skype and even

introduced him to her parents with her webcam.

With monthly

earnings of about $150 some of the women invest in other ventures.

Sathi, for instance, has used her savings to turn her parents' stall

into a rural supermarket, setting a whole new trend. It sells first-aid

kits, USB sticks, medicine, toys, DVDs and even special kits for

repairing mobiles that have dropped into the water on a paddy field.

There is a small parking area outside for bicycles. The undertaking has

turned out very well and the budding entrepreneur has invested in a

generator, so she can show Bollywood movies, even when there's a power

cut.

The info-ladies project is still a pilot scheme. It has

failed in conservative areas where it is very difficult for women to

have a job and where the number of migrants working overseas is too low

for the Skype service to show a viable return. In the areas where the

business model works, there are plans for the women to be paid to carry

out market research. It has also been suggested that they should use

tablet computers, which are more dust-resistant than conventional PCs.

With this version new recruits would need to find $2,000 to buy into the

info-lady franchise.

This article appeared in Guardian Weekly, which incorporates material from Le Monde